Carleton-Faribault PAR Collaboration

Project background

In October 2018, Carleton College, in collaboration with the Faribault Public Schools, Somali Community Resettlement Services, and Community without Borders, received a grant from AmeriCorps (overseen by the Corporation for National and Community Service) to design and implement a participatory action research (PAR) project. The co-PIs for the grant are Anita Chikkatur (Department of Educational Studies, Carleton College), Amel Gorani (director, Center for Community and Civic Engagement, Carleton College [CCCE], year one), Emily Oliver (associate director, CCCE, years two and three), and Sinda Nichols (director, CCCE, year four). The grant was renewed twice: once in October 2019 and again in October 2020. In October 2021, Carleton was provided with a no-cost extension to use the remaining funds.

The town of Faribault, which is located in Rice County, Minnesota, has a population of approximately 23,000. In the past decade, Faribault’s population has gone through a rapid demographic change, partly because of its growing Somali population. According to data from the Minnesota Department of Education, 19 percent of students in Faribault were identified as Latinx and approximately 7 percent were identified as Black in the 2009–10 school year. By 2018, 20 percent of the students were identified as Latinx and 20 percent were identified as Black, with the majority of the Black population in Faribault being identified as coming from an African immigrant or refugee population, mainly Somali. This rapid change in student demographics in less than a decade has not led to parallel changes in the teaching force in Faribault. Like many small towns adjusting to such changes in the racial and ethnic make-up of their communities, Faribault has been facing challenges in terms of ensuring that all students complete high school and pursue higher education.

The grant has funded various community research groups that worked with staff and faculty from Carleton College to learn about research methods and ethics and to implement various ways to collect information about the experiences of Somali and Latinx students and parents in Faribault. Because this project has involved students, parents, teachers, administrators, and university staff and faculty, it has drawn on principles of youth participatory action research (YPAR), teacher action research (TAR) and community-based participatory action research (CBPAR).

Please see local news coverage about the grant and Carleton College’s initial announcement about the project.

Project objectives

The project’s main objective was to understand the experiences of three different stakeholder groups at Faribault High School: Latinx and Somali high school students, their parents, and the teachers who work with those students. The project sought to have the stakeholder groups define, explore, and understand both the challenges they face and the assets they possess in order to move away from deficit-focused understandings and solutions while maintaining a focus on documented disparities in racial minority students’ educational experiences and outcomes.

This grant aimed to bring together college faculty who have expertise in participatory action research theory and methods, college staff who have expertise in civic engagement philosophy and in developing sustained relationships with community partners, and community members who have personal and professional expertise in their lived context.

While Carleton College faculty and students have a long history of conducting public-facing research in local communities, including Faribault, social justice–oriented research conducted by university-based researchers differs from participatory action research. Andrea Dyrness explains that:

In contrast, she argues that participatory action research assumes that “‘ordinary’ people also produce knowledge that is useful in struggles for change, and [that] the research process itself could be an important arena for making change” (Dyrness, 2011, p. 203). This difference was crucial to how the research process was designed in this project with community researchers taking the lead on deciding what and how to research.

The PAR framework provides one way for critical reflection on problems of social inequity, attempting to move beyond the divisions that often exist between universities and their surrounding communities. This project also sought to move beyond recent conceptualizations of civic engagement that focus on the educational value of community engagement for college students (Bailey, 2017), the possibility of transformative learning for college students (Giles, 2014), or as an element in the pedagogy and curricula of college faculty (Grain & Lund, 2016). The project instead was envisioned as a way for Carleton College to foster reciprocal collaborations that center community needs and that support community partners in making Faribault a place where all communities can thrive.

Bailey, M. S. (2017). Why “where” matters: Exploring the role of space in service-learning. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 24(1), 38-48. https://doi.org/10.3998/mjcsloa.3239521.0024.104

Dyrness, A. (2011). Mothers united: An immigrant struggle for socially just education. University of Minnesota Press.

Giles, H. C. (2014). Risky epistemology: Connecting with others and dissonance in community-based research. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 20(2), 65-78. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.3239521.0020.205

Grain, K. M. & Lund, D. E. (2016). The social justice turn: Cultivating “critical hope” in an age of despair. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 23(1), 45-59. https://doi.org/10.3998/mjcsloa.3239521.0023.104

Torre, M. E. (2009). PAR-Map [PDF file]. Retrieved from https://actionresearch.mit.edu/sites/default/files/documents/PAR-Map.pdf

Click each year for research updates!

Year 1

Year one teams

The parent team consisted of five Latinx parents, all of whom had older children not yet graduated from high school and currently had a child enrolled in Faribault High School. The team was recruited by Cynthia Gonzalez of Community without Borders. Cynthia is also a member of the team and served as a translator and liaison between the team and the Carleton team.

During the first year, a key theme that emerged during weekly meetings of the Latinx parent research team was their sense of urgency in terms of ensuring that more Latinx students graduated from high school. Each team member could name several Latinx children who had failed to finish high school in Faribault, including some of their own children. This team also felt that the Latinx residents in Faribault did not have a coherent sense of community, possibly because there was no central gathering place for the community, such as a cultural center. The parent-researchers were invested in and passionate about finding out more about Latinx parents’ experiences with the high school and decided to develop a survey for parents. The survey project received approval from Carleton College’s IRB (institutional review boards).

The parents wanted to create a baseline of knowledge about Latinx parental experiences so that they could decide on what specific changes need to be made. They decided to host a community event for Latinx parents to come and take the survey. Despite their great efforts to get the word out about the event (e.g., posting flyers at local businesses frequented by Latinx residents, creating a Facebook video about the event, asking the high school to mail flyers to all Latinx parents), only five parents came to the event. The parent research team was disappointed, but decided to keep collecting survey responses through other means, such as going to Latinx restaurants in town. They collected a total of 20 responses by the end of May 2019. The survey results were analyzed by three Carleton students supervised by a faculty member in the mathematics and statistics department.

The Latinx parent team presented their preliminary findings to school district officials in June. They shared the following results that they found surprising and/or informative from the initial survey analysis:

- Most parents had relatively low levels of formal education, which impacted their ability to support their children with their homework.

- The majority of parents said that their English levels were “okay” (14 of 20), and the same number said that they spoke Spanish mostly at home.

- Eleven out of 18 parents said that they had attended at least one parent-teacher conference this year.

- While 11 out of 18 parents said that they trusted their children’s teachers, 14 parents said that they did not know all of their children’s teachers.

- Twelve out of 17 parents said that they did not know their children’s counselors.

- A majority of respondents (16 of 18) felt respected by school personnel.

- Few parents knew about after-school academic support and enrichment programs offered by Faribault High School, and those who did had children enrolled in the programs.

- Thirteen out of 20 parents said that their children did not receive help with their homework at home.

The parent team ended their presentation to the school district officials with the following messages:

- We want to bring awareness of why Latinx students are not graduating.

- Because we cannot always support our students with their studies, we want students to get extra support.

- We want a program for Latinx students that inspire our children to feel confident and included in all aspects of schools in Faribault so they can be successful.

- We want school to be a place where they feel confident and can get support.

- We want ourselves as parents and our young people to build trusting relationships with all of you.

The Somali parent team consisted of five Somali parents who had children in the Faribault School District. Because the Carleton team members spoke no Somali and the Somali parents spoke limited English, the team also included two interpreters (a school district employee and an employee from Somali Community Resettlement Services). Because of some initial miscommunication, only one of the parents on the team had a child enrolled at the high school, so the team decided to focus more broadly on the school district rather than just the high school.

The parent research team decided to hold a community listening meeting for the Somali parents in Faribault to gather information about community members’ experiences with the school system. During the listening session, the facilitators asked questions developed through a collaborative process between the Somali parent research team and the Carleton team. Somali parents were recruited to the listening session through flyers distributed through the schools and community organizations as well as through word-of-mouth recruiting by members of the parent research team. This research project received approval from Carleton College’s IRB.

Listening sessions flyers in English and Somali

On April 28, 2019, parents were organized into small groups with one facilitator (one of the parent research team members) and one or two notetakers. The discussions were all in Somali. The notetakers included Somali community members from Faribault, Northfield, and Twin Cities, who all took notes in English. Before starting the discussion, the facilitators explained the purpose of the meeting and asked each parent if they were willing to participate. Once their consent was obtained, the parents were then asked a few demographic questions.

No names were recorded to maintain anonymity and to allow parents to be honest in their answers.

Twenty-nine parents attended the listening session. All of the participants identified as female. One participant did not have children in the public schools; the other 28 participants had between one and eleven children. The participants had lived in Faribault for between two and thirteen years, with a majority (22) having lived in Faribault for six or fewer years. These parents represented 102 students enrolled in Faribault Public Schools.

These were the main themes that emerged from the listening session:

- Concerns about the English language learning and English as a second language (ESL) programs at Faribault Public Schools, especially at the high school

- Concerns about Somali students not graduating on time

- Need for increasing religious accommodations and supports

- Need for more Somali teachers, paraprofessionals, and mentors

- Need for more academic tutoring and support for Somali students, especially during after-school programming

- Experiences of Somali students and parents with racial discrimination, cultural misunderstandings, and lack of encouragement

- Reinstatement of community-organized busing, especially during the winter months

- Concerns about their children’s use of technology

- Need to decrease class sizes and increase school choices

The Somali parent research team wanted their findings to be shared with the school district in the form of a written report, which was prepared by Anita Chikkatur. This listening session, as well as an external evaluation of the research team members’ experiences, made it apparent that the Somali community felt very clear frustration with the school district’s lack of response to their concerns. As parents at the listening session and members of the research team noted, the community has had multiple opportunities to share their experiences and their recommendations about how to support better Somali students in the district but has not seen substantial changes in school policies or practices.

The student team consisted of six Latinx high school students and six Somali high school students. They were recruited by the school administrators.

During their weekly meetings between January and March 2019, the student team decided that their main question centered on the lower high school graduation rates of Somali and Latinx students compared to their white peers. Based on intense discussions about their own experiences at Faribault High School, the student team generated several possible reasons for this disparity:

- Students of color often have to work to support family.

- Students of color are not being given the same resources or opportunities.

- Mental health reasons.

- Students of color are not as involved in school.

- Teachers treat students of color differently (teachers relate more to students who are like them).

- Counselors aren’t informing students.

- Parents of color are not as involved.

- Students learning English and students new to the U.S. are isolated.

The team decided in April 2019 to conduct a survey of their peers to assess their experiences in the school. After discussing the (im)possibility of obtaining parental permission for all students under 18 at the school (as required by the Carleton’s IRB), the student team decided that their survey results would be shared only within the school, which meant that the study was not considered “research” as defined by IRB. Given that the main impetus for PAR projects is change in a local context, this decision made sense. The survey was randomly distributed to second-period classes by the school’s dean of students. The survey was completed by over 180 students, and survey results were analyzed by the students with some assistance from a Carleton student.

In June 2019, the student team presented these results and some preliminary analysis to the school administrators, who planned to study the results further over the summer to determine what changes might need to be made at the school to address student needs. The student team members’ openness to learning from and about each other and their willingness to share their experiences meant that an important goal of PAR projects—building community across differences—was met. While the survey results will not be shared publicly, a report about the student team’s process will be shared more broadly.

Much of what the student team shared about their experiences at Faribault High School resonates with educational research findings, particularly from research studies conducted in schools with diverse student populations. For example, the student team’s comments about how teachers seem to interact differently with white students in informal situations resonate with Bettie’s (2014) research on a group of white and Latinx high school students in California. She found that teachers often formed friendlier relationships with students who are “like” them—white and middle-class. Similarly, Lee’s (2005) ethnography of Hmong American students at a Wisconsin high school notes that the “good” students at her site were the ones who were on “friendly terms with faculty and staff…They [could] engage in witty banter with teachers and administrators inside and outside of school” (p. 28). These kinds of interactions with teachers required a certain level of fluency in English and mainstream culture that not all students had access to.

Similarly, students’ comments about their negative experiences resonate with research findings on stereotype threat and student belonging. This body of research has demonstrated the importance of small gestures—such as knowing students’ names—for students who may not already feel like they belong at an educational institution because of their race, class, gender, or other social identities. While some of the slights described by students may seem trivial, researchers noted that students “whose groups are stereotyped or otherwise stigmatized tend to be uncertain of the quality of their social bonds” at their schools (Spencer et al., 2016, p. 424). This kind of uncertainty can make them “especially sensitive to signs that they do not belong,” including interactions that may seem “innocuous to others” (p. 424).

The teacher research team consisted of six white teachers at the high school.

After two training sessions about research and racial equity in March and April 2019, the staff research team decided to interview Latinx and Somali students and graduates about their experiences at Faribault High School to investigate the factors that support or hinder high school graduation for Latinx and Somali students. This was a practitioner inquiry research project where the teachers focused on their teaching context to generate ideas about how to improve their teaching practices and to ensure that they are effective for all students. Research indicates that “the effectiveness of practitioner inquiry is integrally connected to teachers’ sense of accountability, which is strongly activated by a desire to improve the learning experiences of students most at risk” (Nichols & Cormack, 2017, p. 7).

The team’s main research question was “How can Faribault High School provide an equitable and valuable education to prepare racially, culturally, ethnically, and linguistically diverse students for postsecondary opportunities?” A graph about teacher consultation research (Source: General Teaching Council for Scotland)

To answer this question, the teachers had planned to interview two groups of participants:

Teacher research team’s definitions of “equitable” and “valuable” Somali and Latinx young people who were students at Faribault High School and did not graduate—The assumption being that in order to move on to postsecondary options that require a high school diploma, students have to stay and finish high school.

Somali and Latinx students who are currently enrolled—The teachers wanted to find out more about their experiences in school, their ideas and hopes for their futures, what they hope to do post–high school. Students are best positioned to inform teachers about what is working for them and what’s not as teachers try to figure out how to ensure that the high school is providing an equitable and valuable education.

Most of the interviews were conducted in English with a few conducted in Spanish. Because none of the teachers are fluent in Somali and it was decided that the presence of an interpreter would make it difficult for students to express themselves, the teachers decided to only interview Somali students who are able to communicate in English. This study received approval from Carleton’s IRB.

The teachers interviewed eighteen current students and three young people who had attended the high school. More than half the students were enrolled in the English language program. Over the summer, one of the teachers coded the data, and all of the teachers prepared a presentation for the high school staff based on this analysis. They spoke to their fellow staff members at a staff meeting on October 9, 2019.

The main findings from the interviews included the following:

- Students appreciate staff who help.

- Other students can create a less welcoming environment.

- Students see themselves as individuals first.

The teachers noted that the students shared almost nothing that was negative in terms of their interactions with staff members, noting that this absence could be due to the fact that they, the interviewers, were teachers. They noted that the students expressed concrete goals for their futures, including college degrees, stable jobs, helping their parents, making their parents proud, and buying a home for their parents, as well as the more abstract goal of being happy. The students noted that a recent change in administration had led to positive changes in their school.

The students they interviewed also faced challenges during their time at the high school, such as having to make decisions about college and explaining everything to their parents, navigating tensions among students, and not feeling represented on the school’s student council. The students also spoke about how race, culture, and language impacted their experiences at the school. The teachers chose the following quotes as representative of these impacts:

- “It is harder, only because I have to work twice as hard to figure it out and explain things.”

- “You just have to be the first one to start a conversation.”

- “Harder for Somali girls to join sports” (family limitations).

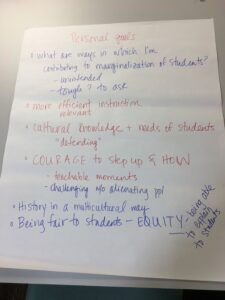

The teachers encouraged their fellow staff members to make sure that they prioritized student voices and relationship building in their interactions with students. They appreciated the creation of a district equity team and site equity team that focuses on parent engagement and education so that all parents feel empowered to support their children as they navigate their way to a positive future. They also noted that the school should ensure more equity in participation among different groups of students in school clubs, organizations, and sports teams. Personal goals, and hopes and dreams of the teachers

Year one highlights

- Four community research teams created and carried out their own research plans.

- Weekly team meetings created opportunities for students and parents to develop a sense of community among themselves.

- Opportunities were created for students and parents to share their experiences and ideas with the school district officials.

- The student team and Latinx parent team developed a clear sense of purpose and ownership over the project.

- Stronger relationships were developed between the Carleton team and members of the high school administration.

- A stronger relationship was developed between the Carleton team and Community without Borders.

- Carleton team identified useful PAR resources in English and Spanish.

- Carleton team created English-Spanish and English-Somali brochures about academic support programs at the high school to increase awareness of the programs among the Latinx and Somali communities.

- Featured as a Grantee Spotlight in the June 2019 CNCS Office of Research and Evaluation newsletter.

- Presented with parent community researcher at 2019 Midwest Campus Compact Conference (Abdullahi, A., Chikkatur, A., Gorani, A. [May 2019]. Bridging the cultural and communications gap in Participatory Action Research [PAR]. Midwest Campus Compact Conference, Minneapolis, MN.).

Year one conclusions

It’s been clear from the work of all four community research teams in Faribault that all stakeholders are incredibly concerned about ensuring that all students graduate from high school on time. All teams identified the low graduation rates of Latinx and Somali students as a primary concern. The discussions during the weekly team meetings of the student and parent teams also have made clear that there are gaps in communication between students, parents, and school officials. For example, when the Latinx parent team presented to school district officials, they commented later that they had never met the high school’s assistant principal or dean of students. Similarly, an informal conversation between Anita and the district’s English language program coordinator about the report on the Somali parent listening session indicated that there might be conflicting (though equally important) goals in the district. While the Somali parents expressed great concern about Somali students not graduating from high school in four years, the school district sees English proficiency as an important goal. Depending on when students start their education in the United States, it might take them longer than four years to achieve that goal. Research on bilingual education, for example, has found that academic English proficiency can take five to seven years to develop (Hakuta, 2011). These examples indicate that one needed crucial change is to develop better and more consistent channels of communication between school district officials, teachers, parents, and students about their goals and needs—an important finding in its own right.

Story Stitch game by Green Card Voices

The two parent teams’ and the student team’s experiences demonstrated the clear and important need for taking time to build community and connections within PAR teams. We found Story Stitch, a Green Card Voices game, to be a useful tool across those groups. The parent teams appreciated being able to share experiences with other parents. The external evaluator’s report about the Somali parent research team noted, for example,

“prior to their participation in the research, they believed that their challenges were unique to them and that the rest of Somali community was doing well. However, being in the same room with many parents made them aware that they were not the only ones facing these challenges. The realization that the barriers and difficulties that their children were experiencing were shared by the wider community reduced the stigma and fear of speaking out about these problems.”

Similarly, the student team expressed their appreciation for getting to know each other, and the importance of the time spent sharing stories and experiences was evident in a moment during their presentation to the school officials. The assistant principal asked them what they could do to encourage more students of color to get involved, and a Latina student said that the school needed to be aware of the barriers that Somali students faced because of the timing of Ramadan and how fasting during that time impacted their ability to get involved in sports. It was clear that students had listened carefully to each other’s individual and cultural experiences.

Identifying culturally relevant and appropriate resources to share with the community research team has been a crucial factor in enabling and empowering them to do their work. For the student team, having another youth research team work with them around defining youth participatory action research (YPAR) and research methods was key to getting the Faribault students interested and invested in PAR. For the Latinx parents, starting with a viewing of the documentary Madres Unidas, which is about a group of Latinx mothers in Oakland conducting research in their children’s school, provided an incredible framework and example. For the teachers, providing readings about practitioner action research and a workshop on racial identity and privilege provided a base for their interview study with parents. In contrast, being unable to identify culturally and linguistically appropriate resources for the Somali parents proved to be an obstacle in getting across some of the main components of PAR, which highlighted the need for culturally relevant materials.

It’s been both exciting and logistically difficult to support four PAR teams at the same time, especially as the Carleton team has tried to provide materials and resources in three languages (English, Spanish, and Somali). Conversations with other CNCS grantees (including the Smith College, University of Cincinnati, and University of Wisconsin–Whitewater teams) has made the Carleton team realize that our CNCS project has elements that make sense for our context and make ours a logistically complicated project. For example, compared to Smith College (the only other small college among the grantees), we are working with both adults and minors and with community organizations that are new and not well resourced. We have also realized how valuable it has been to have Carleton team members who can at least understand Spanish when we compare our experiences supporting the two parent teams (none of us at Carleton have even a basic knowledge of Somali). We have reached out to community organizations and people of Somali descent who work with Somali communities in Minnesota; these connections have been helpful with this year’s CNCS grant work and will continue to be helpful for future collaborative projects in Faribault.

The external evaluation of the Somali team made it clear that the parent-researchers did not see participatory action research as the framework driving the work they did. There was confusion about the distinction between parents as researchers and parents as participants, even on the part of the external evaluator. It was helpful, though, to have the external evaluation report because it indicated clearly that the Somali parent research team’s occasional resistance and reluctance to research project stemmed centrally from a deep-seated sense of skepticism that anything would change in the school district. As noted earlier, they felt that they had fruitlessly expressed many times to the school district what Somali parents and children need. Based on the experiences and findings this year from the Somali parent team, the Carleton team has decided to keep a focus on the Somali community but to work with a different set of Somali community members next year.

Logistics on the Carleton side, especially around paying the community researchers, was also a steep challenge, taking up many hours of the CCCE (Center for Community and Civic Engagement) staff, including those who did not initially have direct responsibility for this project. We have learned that the kind of vision a participatory action research project has for the collaborative relationship between community members and the college is different from the relationships imagined in academic civic engagement class projects or in volunteer work by students.

Hakuta, K. (2011). Educating language minority students and affirming their equal rights: Research and practical perspectives. Educational Researcher, 40(4), 163-174. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X11404943

Year two objectives

Drawing on PAR principles, in the first year, each community research team spent time getting to know each other, identifying critical problems pertaining to their community within the school district, deciding on a way to gather information about these problems from the broader community, and presenting this information back to the school district. In the second year, the focus was on action. The action aspect of participatory action research is crucial to what makes PAR projects different from traditional research projects. Researching and theorizing about systems of inequity without proposing and carrying out changes would only replicate those systems. Action researchers make a fundamental commitment to “bring about change as part of the research act” (Brydon-Miller et al., 2003, p. 15). The second year of the project focused on action plans based on the first year’s research as well as additional reflection and research as necessary.

In the second year, two of the research teams continued in a similar format:

- The Latinx team continued with the same five members to learn more about the educational system and their own culturally based ideas about education.

- The student team continued with four of the same students from the first year and eight new students. These two teams met every week from October to December 2019. Because of the challenges posed by the onset of COVID-19, the plan to resume these weekly meetings in March had to be adapted.

Rather than having a Somali parent team during the second year of the project, the Carleton team decided to support a Somali young adult research team instead. This allowed the Carleton team to provide support in English, since it lacked Somali language fluency. Finally, rather than having a research team of teachers in the high school, two equity teams were formed—one at the district level and one at the high school—to implement action plans based on the findings of CNCS research teams from the first year.

Year two teams

Consisting of the same five parents as the first year, the team continued to learn about each other and about the educational system. During their weekly meetings, the team discussed what “education” meant to them, especially within the cultural context of their families and their communities. They watched the documentary Precious Knowledge and attended a lecture by Dr. Angela Valenzuela at Carleton College to learn more about the struggle for ethnic studies in K–12 schools. They also learned about educational systems and community organizing from guest speakers from Faribault and the Twin Cities. They learned how to use technological tools, such as Google Docs and Zoom, when we had to switch to online meetings because of the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

As PAR scholars have noted, these projects take time, and the process is often messy and unpredictable. There will be inevitable conflicts of interests, ideas, and identities. The principles of participatory action research encourage everyone involved in the research to “excavate and explore disagreements and disjunctures rather than smooth them over in the interests of consensus” (Torre, 2009). The Latinx parent team experienced such a conflict in late fall, when there were tensions around how each member was contributing to team meetings and communicating with each other. The team, without the presence of the Carleton team, had a discussion about how to resolve conflicts, how to listen, and how to communicate more effectively, using tools and strategies from StirFry Seminars & Consulting.

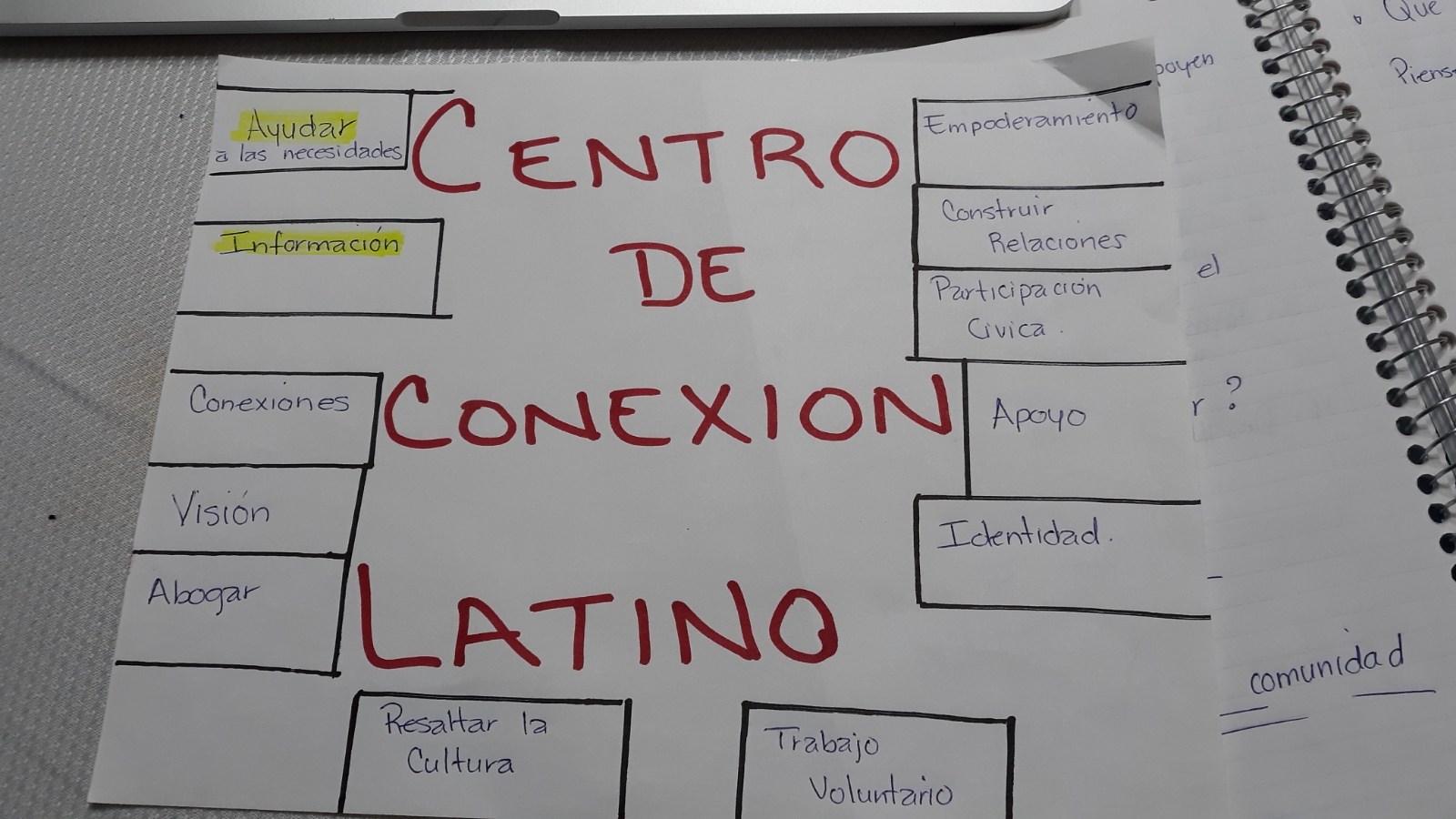

The team decided that they want to start a Latino parent center in Faribault. Tentatively named Centro de Conexión Latino, this center will provide a way for the Latinx parent team to connect with the broader Latinx parent community and expand the population of involved parents. To support Latinx parents who want to understand and more effectively access the educational system, the center will empower them with the information the parent team has at their disposal and connect them with the different programs that exist in the community and within the school system. The center’s “pillars” include support, advocacy, building relationships, community, identity, empowerment, volunteerism, and civic participation.

Because the team included eight new students, the team used some of the same community-building methods as last year, including using the Story Stitch game (Green Card Voices) to get to know each other. At the weekly meetings, the students examined their own experiences at the school, exploring how social groups at the school were based on racial and other social identities. They learned about research methodologies and research ethics, and they shared their visions for a more inclusive school through a vision board experience.

Unfortunately, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic meant that they were unable to regroup after winter break and formulate a research question and plan. Two of the team members did meet a few times with the Carleton co-PIs and started an Instagram account to post about some of their experiences during the pandemic. We also posted about what the team learned about youth participatory action research over the past two years (Instagram handle: youthgroup_for_a_better_tmr). If we are able to have another student group next year, they will be asked if they want to use the Instagram account to post about their work.

Unfortunately, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic meant that they were unable to regroup after winter break and formulate a research question and plan. Two of the team members did meet a few times with the Carleton co-PIs and started an Instagram account to post about some of their experiences during the pandemic. We also posted about what the team learned about youth participatory action research over the past two years (Instagram handle: youthgroup_for_a_better_tmr). If we are able to have another student group next year, they will be asked if they want to use the Instagram account to post about their work.

A couple of the students’ vision boards

Based on the Carleton team’s lack of Somali language abilities, the two co-PIs decided to recruit a Somali young adult team; the Carleton team could work with the young adults in English, and the young adults’ bilingual abilities would help them work with the community, depending on what they chose to do. The team consisted of young people who had already worked with the Carleton team during the first year of the CNCS project: four of them were on the high school student research team and one of them worked with the Somali parent research team as an interpreter. During their weekly meetings in the fall, the team discussed their experiences as students in the Faribault Public Schools and their ideas about what worked or did not work to support them. They also learned more broadly about the Somali community in Minnesota through examining statistics and watching a documentary about the role of poetry in Somali culture. They also had a meeting with an alumna who had recently graduated from a four-year college. The team decided to record a series of podcasts about their experiences. Because of COVID-related delays, the team was only able to record a draft of one episode this year, which focused on their experiences in the public schools in Faribault. They plan to re-record the episode next year, especially making sure that all team members’ voices are included, along with additional new episodes.

Based on the findings from year one research conducted by the Somali and Latinx parent, teacher, and student teams, the high school administrators created a school-based equity team this year as part of their action plan. The equity team, led by the two assistant principals, developed all-staff training sessions about racial equity and anti-racism. The assistant principals spoke about the challenge of not having a lot of time for professional development in general in the school district. Some of these sessions included the following:

1. They watched a video (“Silent Beats”) that addresses biases and assumptions that led into a discussion about how those play out at their school and generating strategies to combat assumptions and biases.

2. They had a “history walk”: examining 50 different policies and laws (e.g., Supreme Court decisions) that perpetuated racism explicitly or led to racist outcomes in education. The assistant principals framed the discussion by having the teachers think about the hundreds of years of policy that perpetuate oppression, and reflect on their role in the current time to work on this deep-seated problem. They wanted to make it clear that while the current situation was not necessarily the teachers’ fault, it was their responsibility to change it. This conversation led the teachers to examine grading policies and outcomes at the school and to a series of summer professional development sessions about grading equity based on discussions of the book Grading for Equity by Joe Feldman.

3. There was a full-day training session for all teachers in the district that examined how anti-racism manifests in the “head, heart, hands.” The book Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain by Zaretta Hammond provided the main framework for this session.

Year two conclusions

Effective communication within and across stakeholder groups has emerged as a key factor in shifting school, community, and individual practices to more effectively support Latinx and Somali students and families in Faribault. The Latinx parent team especially has insisted that parents should be involved more completely in the decisions that the school makes about and for their children. When the school sought their advice about the new program, RISE (Realizing Individual Student Excellence), for example, the parents spoke about how a similar support program in Northfield often left parents out of conversations. The parent research team expressed very strongly their desire to be informed and educated about what support and advice are being given to their children by school personnel. As one member put it, “Who else knows our children better than us, as parents? Sadly, here, our youth complete eighteen years and already they’re of legal age for the society. But before they turn eighteen, many of them don’t have the sufficient maturity to choose or determine the right school, the career.” The high school administrators have taken substantial steps to improve communication between the school and Latinx and Somali parents, though there are still improvements to be made. For example, it took the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic for the school district to develop video guides in Spanish and Somali to help parents access the district’s online parent portal.

Because of COVID-related school closings and statewide stay-at-home orders, we were unable to continue the weekly in-person meetings of the community research teams.

Latinx parent team

We transitioned to virtual meetings with the Latinx parent team after spending three meetings helping members become familiar with Zoom, Google, and other online tools. The Latinx team has met with community leaders in Faribault and the Twin Cities to learn about community organizing and civic participation, learned more about community-led efforts to diversify school curriculum, and practiced facilitation skills, as the meetings were facilitated by the Latinx parents rather than the Carleton co-PIs.

Somali young adult team

The Somali young adult team was mostly able to transition to online meetings, though the young adults’ college responsibilities, work schedules (many team members took on extra shifts to support their families because of the economic impacts of the pandemic), and the timing of Ramadan made it more challenging for this team. It was also challenging to provide them with technical support and the right equipment because we were not able to meet in person. They recorded a draft of an episode about their experiences in Faribault schools. If there is a third year of CNCS funding, the team plans to re-record that draft episode and to make five additional episodes.

Somali and Latinx student team

It was most challenging to connect with the Faribault High School students, given that their weekly meetings had always been right after school, near their high school. The Carleton team was able to reconnect with four of the students, who decided that they wanted to start social media accounts to post positive and encouraging messages to their peers. They all noted that the transition to distance learning was challenging—they missed being able to interact with their friends and learn from and with them, as well as more easily access support from adults.

Achievements and ripple effects for year two

- In-person weekly meetings (October to December 2019) with three community research teams to learn about community building and participatory action research, online weekly meetings with Latinx parent research team and Somali young adult team (April to June 2020).

- Video made by Latinx parent research team to encourage Faribault’s Latinx community to vote in school levy elections in November 2019.

- Open forum about racial inequities at the school, which was held outside this summer and attended by two members of the Somali young adult

- Faribault High School assistant principal, Joe Sage, chosen by Carleton College for the Presidents’ Community Partner Award through Minnesota Campus Compact.

- Inclusion of a Latinx parent team member and the Carleton co-PIs in post-COVID discussions about how to make online platforms more accessible for Somali and Latinx parents.

- Inclusion of two Latinx parent team members, one student team member, and co-PI Chikkatur in the interview process to hire staff for the new RISE program.

- Somali youth adult team recording a draft of a podcast episode about their experiences in Faribault schools.

- Development of Carleton College course “Community-Based Learning & Scholarship: Ethics, Practice” to be co-taught in fall 2020 by CNCS Latinx parent team community researcher Cynthia Gonzalez and co-PI Emily Oliver. They secured an internal Public Works award (sourced from a Mellon Foundation grant) to support this course.

- Development of Carleton College course “Refugee and Immigrant Experiences in Faribault, MN,” to be taught in fall 2020, co-planned by co-PI Anita Chikkatur and St. Olaf colleagues. The course focuses on challenges and opportunities for people with refugee and immigrant backgrounds and for educators and community leaders to create supportive contexts that meet these communities’ needs and aspirations.

- Latinx parent research team member, Cynthia Gonzalez, asked to serve as a “cultural adviser” to the Faribault School Board.

- School practices: (1) ending the “no hood or hat” policy, which resulted in fewer disciplinary actions against students, (2) changing morning supervision routines to ensure that every student has at least three positive interactions with an adult before first period, (3) monthly meetings between high school administrators and Somali and Latinx parents, (4) creation of high school and district equity teams, and (5) phone calls and letters to parents sent in Spanish and Somali in addition to English.

- Development of a new academic support program, Realizing Individual Student Excellence, or RISE, to address concerns raised by students and parents during year one about providing academic support during the school day.

- All-staff professional development about racial equity and anti-racism at the school.

- Summer professional development sessions focused on grading equity (25 teachers attended the first meeting on July 19, 2020).

- Attendance of 14 students, along with Assistant Principal Shawn Peck, at a youth virtual leadership summit sponsored by the National Youth Leadership Council.

- Presentation by Cynthia Gonzalez (Latinx parent research team), Amina Aden (Somali parent research team), and Emily Oliver and Anita Chikkatur (grant co-PIs) at the CNCS research summit in Washington, DC, in September 2019.

- Presentation of a video made by Latinx parent team about their PAR experience at the “Imagining America” gathering in October 2019 as part of a PAR workshop led by co-PI Anita Chikkatur.

Year 3

Year three objectives

In the third year (October 2020–September 2021), the grant supported community teams’ continued research as well as actions that responded to the research conducted by various teams in the first two years. Most prominently, the grant supported staffing for a new program, RISE (Realizing Individual Student Excellence), an academic and social support program for first-generation students, students of color, and students from low-income backgrounds at Faribault High School. The program started in fall 2019, partly in response to the research done by parent and youth research teams during the first year of the PAR project. RISE is supported by AmeriCorps Promise Fellows and now exists at the middle school as well.

The Latinx parent team continued to organize and empower Latinx parents to support their children’s education. Meanwhile, the YPAR team at the high school was facilitated by a counselor—a move that was meant to increase capacity and expertise at the high school, and one that also made sense during the COVID-19 pandemic, since Carleton’s travel and research guidelines prevented the co-PIs from being at the high school. The grant supported the Somali young adult team to record and produce several podcast episodes about their experiences in Faribault.

The third year of the grant also supported the work of an external consultant who worked with staff at Carleton’s Center for Community and Civic Engagement (CCCE) to evaluate the college’s ongoing relationships with community partners, with a focus on the PAR project, and to produce a report or guide about how to incorporate more reciprocal and ethical community-based work across Carleton’s campus. This fulfilled an initial goal of the project to integrate the PAR project’s methodologies and findings into Carleton’s curricular and cocurricular community-engagement practices, especially in informing the programs supported by CCCE.

The COVID-19 pandemic continued to impact the health and well-being of community members involved in the PAR project, and it curtailed the ability of the co-PIs to work in person with the community partners. Nevertheless, this year’s grant supported a variety of research and action in Faribault and Carleton.

Note: the granting agency went through a name change from Corporation for National and Community Service to AmeriCorps.

Year three teams

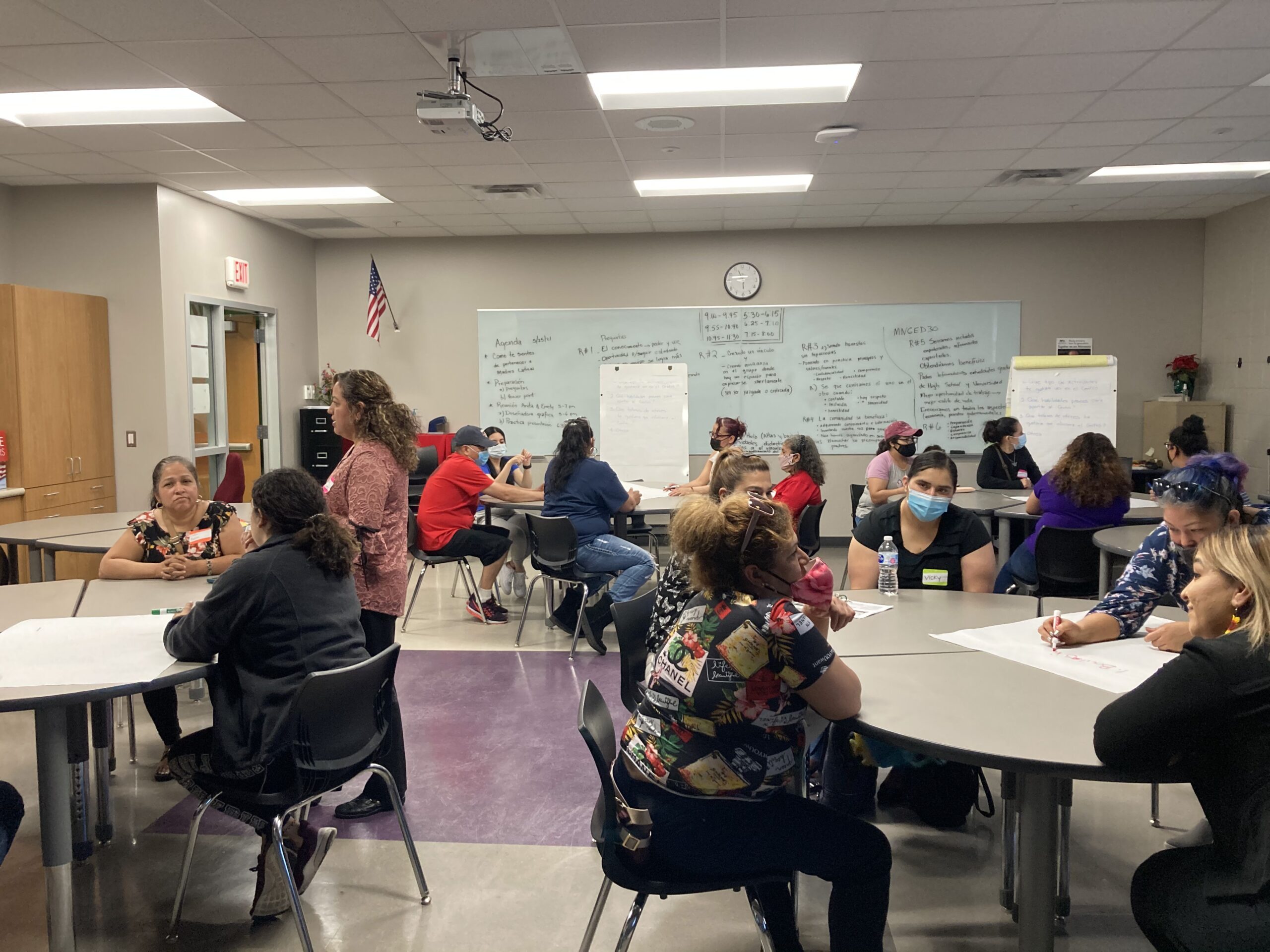

Health challenges, mainly due to COVID-19, heavily affected the team members as did challenges with technology as the team shifted to online meetings. Despite these challenges, the team tried to move forward with their vision for a Latinx parent cultural center, organizing as many meetings as they could. Unlike the past two years, the parents were in charge of organizing and facilitating the meetings themselves instead of the Carleton co-PIs. This shift allowed the team members to develop different skills, and though the work often took longer, they felt more ownership over their work. In June 2021, when some in-person gatherings were possible again thanks to vaccinations, the team held an in-person meeting that was attended by over 20 Latinx parents. They discussed the work being done by the team and engaged in a vision-brainstorming session about what they would like to see at the parent center. The team also presented virtually to various educators and administrators about their work and their desire to collaborate with the school district to empower Latinx parents. The team planned to hold another meeting for parents in fall 2021 as they worked on implementing their first events at the center. They hoped to secure a location for the center at one of the schools in town for at least the first year. They also focused on applying for and securing funding for the center.

This year’s team was facilitated by Brian Coleman, the Career and Equity Coordinator at the high school. Brian met every other week with co-PIs Anita Chikkatur and Emily Oliver to co-develop a curriculum for the YPAR team. This year’s team included four Latinx students and four Somali students, ranging from ninth graders to twelfth graders with a range of academic experiences at the high school. Brian met with the team weekly, initially focusing on building community among the eight students and then moving on to learning about research. Given the context of the pandemic, the YPAR team decided that they wanted to focus on their peers’ experiences this past year with distance learning and to conduct short interviews with 40 of their peers to collect information on that topic. They decided to disseminate their findings through three videos, each in three different languages (English, Spanish, and Somali), aimed at their peers, teachers, administrators, parents, and families. Because of the school year schedule, the final video was produced with the help of co-PI Chikkatur and a Carleton student-researcher. The Somali language versions should be available by the end of 2021.

The team’s most important findings include the following:

- The need for schools and families to understand why students’ motivational levels dropped and mental health suffered during distance learning, which affected their grades. The team wants the community to be educated about how students felt during 2020–2021.

- Without the structure of going to classes, many of the students and their families ended up seeing school as “optional.” Programs such as RISE (supported by this grant and AmeriCorps Promise Fellows), which focused on providing academic support, played an important role in keeping students on track, especially for those whose parents were not as familiar with the U.S. school system.

- Students noted that their parents didn’t understand that distance learning was actually harder and, as one of the student researchers put it, that homework didn’t just disappear. Many of the students were asked to take on other responsibilities, such as taking care of siblings, which made keeping up with distance learning difficult.

Virtual training session about research methods for YPAR team with co-PIs

Virtual training session about research methods for YPAR team with co-PIs

These team members were heavily impacted by the pandemic, having to navigate sickness, online college classes, family responsibilities, and increased need to support their families economically. The team were able to record three additional podcast episodes:

- Ceeb (shame) culture in their Somali community

- Gendered experiences and expectations in their families and community

- Popular culture

The co-PIs participated in the popular-culture episode and were impressed by the team’s engagement with a range of multilingual and multicultural products! All of the episodes are now available on the Somalis Out Loud page on this website.

Year three highlights

The program, started partly in response to the research done by community teams during the first year of this project, was supported by funds from a variety of sources, including this grant. Independently, the high school applied for two AmeriCorps Promise Fellow positions; the fellows would work with the two program coordinators. Co-PI Chikkatur and Latinx research team member Cynthia Gonzalez were part of the team that interviewed potential candidates for the program coordinator positions. While working with 100 students was the initial goal, the program staff worked with over 200 students during the school year, providing academic support and advising and support for social-emotional needs. They also worked to engage parents and families, including preparing packets with school materials and food to drop off at students’ homes. As the YPAR team noted from their research, the support provided by the program was particularly helpful for students of color as they navigated the challenges of distance learning and health and other impacts of the pandemic on their families and communities.

The co-PIs, with the support of a Carleton student researcher, worked on developing the resources on the Participatory Action Research website. The student researcher (Eunice Valenzuela) particularly focused on finding examples and resources in Spanish. The website was used as a classroom resource for the two courses, which focused on Faribault, taught by the co-PIs in the fall. The students in co-PI Chikkatur’s fall course also worked on annotated bibliographies focused on refugee and immigrant education, which are now available on the website. In summer 2021, a Somali language expert was hired again to continue developing the Somali page, and professional copyeditors were hired to edit the Spanish page. This past summer and this academic year, a new student researcher, Ahtziry Tinajero, will be working to update and maintain the website.

One of the reasons Carleton College was excited to apply for and receive a Community Conversations grant in 2018 was to be able to integrate the PAR methodologies and findings into Carleton’s curricular and cocurricular community-engagement practices, especially in informing the programs supported by the college’s Center for Community and Civic Engagement (CCCE). The deep engagement part of PAR projects means that it takes years to build the relationships necessary to work in an effective and ethical way. Co-PI Emily Oliver’s involvement with the project since its beginning has given her the opportunity to learn meaningfully with and from Faribault community members. In collaboration with CCCE’s new director, Sinda Nichols, co-PI Oliver worked with a consultant, Susan Gust, to engage community members (including the CNCS community research teams) and faculty members (including co-PI Chikkatur) to develop a guide that will allow for more reciprocal and ethical community-based work across Carleton’s campus. This guide will also provide a template for other higher education institutions, especially small liberal arts colleges that often have different kinds of resources available for community-engaged work. Gust also worked with a graphic notetaker to produce graphic depictions of various community partners’ understanding of collaboration. The graphics for the Latinx parent team and the YPAR team are available in English, Spanish, and Somali on the Carleton PAR website.

The third year of the grant also supported a two-day workshop in June 2021. Approximately 50 faculty, staff, and community partners participated in “Shaping Our Shared Future: Advancing Equity through Community and Civic Engagement,” an online workshop on June 16 and 17, 2021. This interactive workshop focused on participatory co-creation among community members, students, staff, and faculty, as the CCCE strives to advance social and racial justice through their community-engaged work. External facilitators Susan Gust and Tania Mitchell (associate professor of higher education at the University of Minnesota) helped ground the workshop with their knowledge, research, and deep experience in this work. Tania Mitchell, an internationally recognized scholar in community engagement and critical pedagogy, gave a keynote address on decentering whiteness and advancing racial equity in the classroom and community. Susan Gust, a community knowledge holder and consultant on this project, worked with local Rice County community partners to shape and facilitate the community-collaboration-workshop content, including the development of visual depictions of community approaches to collaboration. The workshop featured structured opportunities for relationship building and participatory processes that elicited participants’ contributions to learning, knowing, and making change and that centered power sharing, positionality, and an equity lens.

Accomplishments and ripple effects for year three

- Fall 2020: Latinx parent team community researcher Cynthia Gonzalez and co-PI Emily Oliver co-taught Carleton College course “Community-Based Learning & Scholarship: Ethics, Practice.” They are co-teaching the course again in fall 2021.

- Fall 2020: Co-PI Chikkatur taught new course “Refugee and Immigrant Experiences in Faribault, MN,” co-planned by co-PI Chikkatur and St. Olaf colleagues. The course focused on challenges and opportunities for people with refugee and immigrant backgrounds and for educators and community leaders to create supportive contexts that meet these communities’ needs and aspirations. Carleton students heard from several guest speakers, most of whom were involved in the PAR project. The students created annotated bibliographies on various topics related to refugee and immigrant education, which are now available on the PAR website.

- Fall 2021: Latinx parent research team member, Cynthia Gonzalez, facilitated a training session for Carleton students about college-community relationships.

- March 2021: Co-PI Chikkatur and Latinx parent team member Cynthia Gonzalez are invited panelists on a webinar on Latinx rural education, sponsored by the Rural Education Special Interest Group of the American Educational Research Association (video).

- June 2021: Brian Coleman, who is a YPAR team facilitator for year three, and co-PI Anita Chikkatur presented at AmeriCorps’ “Civic Engagement as a Catalyst for Community Change: 2021 Research Grantee Dialogue.”

- June 2021: Latinx parent team presentation to over 20 Latinx parents (in-person) and to district and high school administrators (online) about their work and their vision for the Latino parent center.

- June 2021: Presentations by high school YPAR and Latinx parent teams at Carleton College’s “Shaping Our Shared Future: Advancing Equity through Community and Civic Engagement” workshop.

- Summer 2021: Video about the YPAR team’s (year three) research study about students’ experiences with distance learning (English).

- September 2021: Using examples from this project, co-PI Chikkatur is a panelist on a webinar called “Equity in Evaluation” for federal workers through the Office of Management and Budget.

- Ongoing: Instagram account with posts by members of the student research team.

Year 4

Year 4 teams

Consisting of the same six parents as year three, the team focused on building their grant-writing skills this year as they continued to learn technological skills and about the school system. In years two and three, based on their research in year one, the team decided that they wanted to start a Latino parent center in Faribault. Tentatively named Centro de Conexión Latino, this center will provide a way for the Latinx parent team to connect with the broader Latinx parent community and expand the population of involved parents. To support Latinx parents who want to understand and more effectively access the educational system, the center will empower them with the information the parent team has at their disposal and connect them with the different programs that exist in the community and within the school system. The center’s “pillars” include support, advocacy, building relationships, community, identity, empowerment, volunteerism, and civic participation.

In year four, the team applied to three different grants and, in that process, built new relationships with local nonprofit organizations—Healthy Community Initiative, Community Action Center, and Neighbors United—as they had to find fiscal sponsors for their grants. (Because of institutional policies, Carleton College declined to be the fiscal sponsor.) Unfortunately, none of the grant applications were successful. It has been a challenge to find grants that are appropriate for the team’s current needs.

The team also organized three college visits for themselves and several other parents and their children. They visited South Central College–Faribault and Minnesota State University–Mankato in May 2022 as well as Carleton College in June 2022. The team had also planned a parent event in June 2022 to share information about their plans for the center; unfortunately, they had to cancel the event because the venue they had reserved lost power that day because of high temperatures. The team plans to have the event sometime this fall and use the event to introduce themselves to more parents and to reach out and invite school leaders in Faribault.

Visit to South Central College, Visit to South Central College, Visit to Carleton College, organized by Faribault, MN, May 2022 Faribault, MN, May 2022 Madres Latinas team and supported by CCCE director, Sinda Nichols, June 2022

Because of the departure of the school counselor who had facilitated the YPAR team during year three, new facilitators had to be chosen. Luckily, two members of the year one high school YPAR team—Nima Harun and Damaris Garcia—agreed to facilitate the YPAR team. Co-PI Anita Chikkatur, Nima, and Damaris met with the new principal of the middle school (who was an assistant principal at the high school previously) and with the new assistant principal of the high school (who was a member of the staff research team during year one of the project). Based on their existing relationship with Principal Sage and because the high school was in a moment of transition, Nima and Damaris decided that it would be best to have a YPAR team at the middle school. Both Nima and Damaris and the eight middle school students had a chance to learn from and collaborate with YoUthROC, the YPAR team out of North Minneapolis who had provided training and support during year one of the project.

Faribault Middle School YPAR team visit the University of Minnesota to attend YoUthROC YPAR workshop, May 2022

Findings from middle school YPAR team

The YPAR team decided to focus their research on their peers’ experiences at school, on what made them feel safe and what made them feel like they belonged in school. They sent out a survey and received approximately 30 responses. The YPAR team presented to their peers, the principal, and a few teachers at the end of the school year. They asked their teachers to make more efforts to build relationships with them, because positive relationships with teachers made a crucial difference, and they proposed that the school create a “green resource room,” where students could take a break and have positive feedback and support to help them transition back to the classroom. The team was inspired by the “Purple Room” created by students at Brooklyn Center schools—a project that came out of a YPAR team’s findings in those schools. The Faribault team had a chance to meet with youth researchers from Brooklyn Center as part of a YoUthROC workshop they attended at the University of Minnesota.

The middle school YPAR team with facilitators Nima Harun and Damaris Garcia after their presentation at their school, May 2022

Watch this video to see the YPAR team at Faribault Middle School present their findings on a rise in conflicts among students at their school

Strengths and challenges of the project: Reflections by Co-PI Anita Chikkatur

In the original research proposal, this project’s main objective was defined as understanding the experiences of three different stakeholder groups at Faribault High School: Latinx and Somali high school students, their parents, and the teachers who work with those students. The project sought to have the stakeholder groups define, explore, and understand both the challenges they face and the assets they possess as a way to move away from deficit-focused understandings and solutions while maintaining a focus on documented disparities in racial minority students’ educational experiences and outcomes. The work done by the various community research teams in collaboration with the Carleton College team and district and high school staff has foregrounded the needs, concerns, strengths, and assets of the Latinx and Somali communities as the school district works to ensure that their schools are providing all students with an equitable education.

One main result of utilizing a PAR framework, as the original CNCS Community Conversations application required, has been an incredible shift in how parents, students, and community members view themselves in relation to the school district. This shift has been particularly dramatic within the Latinx parent team because the team has been able to continue their work beyond year one and into year two with the same members, thus deepening their connections with each other, with Carleton, and with high school administrators.

Effective communication within and across stakeholder groups emerged as a key factor and challenge in shifting school, community, and individual practices to more effectively support Latinx and Somali students and families in Faribault. The Latinx parent team especially has insisted that parents should be involved more completely in the decisions that the school makes about and for their children. When the school sought their advice about the new program, RISE (Realizing Individual Student Excellence), for example, the parents spoke about how a similar support program in Northfield often left parents out of conversations. The parent research team expressed very strongly their desire to be informed and educated about what support and advice are being given to their children by school personnel. As one member put it, “Who else knows our children better than us, as parents? Sadly, here, our youth complete eighteen years and already they’re of legal age for the society. But before they turn eighteen, many of them don’t have the sufficient maturity to choose or determine the right school, the career.” The high school administrators have taken substantial steps to improve communication between the school and Latinx and Somali parents, though there are still improvements to be made. For example, it took the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic for the school district to develop video guides in Spanish and Somali to help parents access the district’s online parent portal. However, effective communication remains a challenge, and the Latinx parent team is particularly concerned about some key personnel changes at the high school and the school district.

Latinx parent research team meeting

Shifting the perspectives of staff and administrators at the high school and the school district has also emerged as another key challenge. Much of the work being done by the various community teams in collaboration with the Carleton co-PIs has been about coming to “recognize the resilience, ingenuity, and agency that have existed all along among young people and their families from nondominant communities” (Ishimaru, 2019, p. 1). Even with the best of intentions, most school efforts to “engage” parents defaults to deficit views about nondominant parents, about needing to “educate” them about the American school system, and this attitude can lead to families feeling “judged by educators and find[ing] their cultural practices, values, and priorities disregarded or even denigrated” (p. 3). For example, at a December 2020 meeting with staff in the RISE program, a staff member in a local nonprofit organization collaborating with the program talked about parents and students in deficit ways, such as making assumptions about how students lie to their parents and alleging that parents have no idea what’s happening. While the community members and the co-PIs have worked to shift such deficit views, these views remain prevalent. At most, parents are asked about their experiences but not about their expertise. As Ishimaru noted, however, “an equitable collaboration approach begins from the premise that nondominant families (which includes young people themselves, their caregivers, and extended relations) represent a largely untapped source of expertise and leadership for achieving educational equity and justice” (p. 4).

Ishimaru argued that “only when we initiate educational change with nondominant families and communities—and center their priorities, concerns, expertise, knowledge, and resources (rather than that of the system, or of white, middle-class parents or educators)—can we begin to counter the status quo normative assumptions in the system about what and who matters” (p. 51). While the PAR project has attempted to make this case and put this idea into practice, the co-PIs don’t know that the school officials really have taken this idea to heart in how they operate day-to-day or in how they make decisions. At least at the current moment, most of the work that the district is doing “to improve family engagement” has been limited to attempts “to build relationships or foster more welcoming climates without any fundamental change from the assumptions underlying the conventional deficiency paradigm of ‘fixing’ young people and their families” (p. 55). Additionally, as Bertrand and Lozenski note, if the goal of a research project is policy change, “we need to rethink the assumption that simply disseminating findings and recommendations will trigger change” (2021, p. 8).

The work enabled by this grant has demonstrated the necessity of supporting students and parents of color to develop research and community-organizing skills that enable them to have a powerful voice in Faribault schools rather than relying solely on the school district’s willingness and ability to collaborate effectively with parents and youth.

The project’s reach and potential were severely impacted by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Minnesota’s communities of color were disproportionately affected by the pandemic, which was reflected in the health and other challenges faced by many of the Somali and Latinx community members who were involved in this work. Several team members and their family members contracted the virus, and some were severely ill themselves or had to take care of family members who were severely ill. Black, Latinx, Asian, and Indigenous people in the state tested positive, were hospitalized, and died from COVID-19 at higher rates compared to white Minnesotans (Minnesota Department of Health, n.d.). The pandemic slowed down the work of the community teams both because of these health challenges and because of technical challenges. For example, only two members of the Latinx parent team had access to computers, which made it very challenging to organize and participate in online meetings. The Carleton co-PIs did their best to meet immediate needs, including providing computers and technical assistance, to support the teams in being able to continue their work.

For the Carleton co-PIs, it was both exciting and logistically difficult to support several community teams at the same time, especially as the Carleton team has tried to provide materials and resources in three languages (English, Spanish, and Somali). Conversations with other AmeriCorps grantees (including the Smith College, University of Cincinnati, and University of Wisconsin–Whitewater teams) made it clear that our project has elements that make sense for our context and make it a logistically complicated project. For example, compared to Smith College (the only other small liberal arts college among the grantees), Carleton is working with both adults and minors and with community organizations that are new and not well resourced. The co-PIs have also realized how valuable it has been to have Carleton team members who can at least understand Spanish when comparing experiences supporting the two parent teams. (The Carleton team members lack even a basic knowledge of Somali.)

The lack of Somali fluency on the part of the Carleton team greatly impacted the work we could do with the Somali parents in Faribault. The external evaluation of the Somali parent team in year one made it clear that the parent-researchers did not see participatory action research as the framework driving the work they did. There was confusion about the distinction between parents as researchers and parents as participants, even on the part of the external evaluator. It was helpful, though, to have the external evaluation report because it indicated clearly that the Somali parent research team’s occasional resistance and reluctance to the research collaboration stemmed centrally from a deep-seated sense of skepticism that anything would change in the school district. It was also clear that the Somali community in Faribault already had strong community connections and networks because of the community mosque and the Somali Community Resettlement Services office.

Logistics on the Carleton side, especially around paying the community researchers, has been a steep challenge throughout the three years of the project, taking up many hours of the CCCE (Center for Community and Civic Engagement) staff time, including those who did not initially have direct responsibility for this project. The co-PIs have learned that the kind of deep, collaborative relationships between community members and the college staff and the kind of centering of community-identified needs seem quite different from the relationships imagined in academic civic engagement class projects or in volunteer work by students. Carleton College and universities in general have to make changes to the way they do business when it comes to supporting community-based research projects, and it often takes longer than the cycle of one grant to make these changes.

Another challenge that the project has faced over the three years is personnel changes both at Carleton and Faribault. The project’s first co-PI, Amel Gorani, who initiated the project, left at the end of the first year, and Emily Oliver took over as the co-PI. Oliver was able to build strong relationships with the community members in Faribault over the next two years. While her strong relationships supported a more robust relationship between Faribault and Carleton beyond the grant period, she also left Carleton at the end of the third grant year. However, relationships that were built during her time have continued to be fostered by the new staff—for example, Latinx parent researcher Cynthia Gonzalez has lead training sessions about university-community relationships for students working at the CCCE for the past three years.

On the Faribault side, both of the high school’s assistant principals as well as the counselor who facilitated the YPAR team during year three have left their positions. While co-PI Chikkatur and many of the community team members were initially worried about these transitions, these changes do provide the opportunity to think about maintaining long-term relationships between institutions and communities despite changes in personnel. One of the biggest challenges faced by projects such as this PAR project is how to create the conditions for structural changes that often take years to design and implement while personnel and policy changes are occurring regularly. Working through the inevitable changes in the personnel who are involved has to be a part of the answer to this challenge.